Wikipedia

Eddy currents are loops of induced current that arise in conductive components of accelerator magnets when the magnetic field changes in time, and they are undesirable because they distort the magnetic field, introduce time lags, and cause resistive heating; their impact is mitigated primarily by yoke lamination, interrupting current paths in vacuum chambers and ends, ramp shaping, and active or passive compensation.[^1][^2][^3][^4]

Eddy currents in accelerator magnets

In time-varying fields, Faraday’s law induces nonconservative electric fields, which drive closed-loop currents in conductive structures such as iron yokes, end packs, coils, and metallic vacuum chambers, leading to secondary magnetic fields that oppose the change by Lenz’s law and perturb the intended field quality in the good-field region. , , and in the quasi-static limit formalize this behavior and its backreaction on the magnet field.[^5][^1] [@luFirstOperationalExperience2024] [@lu]

These induced currents produce resistive losses and local heating, which is especially problematic in superconducting magnets where excess dissipation and inter-strand eddy effects can drive quenches or long decay tails.[^6][^1]

Magnetic diffusion encapsulates the field penetration into conductive media, giving and the skin depth , so thicker, more conductive, or higher-frequency excitation yields stronger shielding and phase delay between applied and internal fields.[^1][^5]

Solid yokes support large eddy loops and cannot be cycled rapidly without substantial field lag and losses, whereas laminated, insulated steel slices reduce loop area and inter-laminar currents, preserving field quality and reproducibility in time-varying operation.[^7][^2]

Metal vacuum chambers act as shorted turns that shield and reshape the field seen by the beam, introducing dynamic multipoles and phase shifts that depend on wall thickness and conductivity, which can in turn perturb optics parameters like chromaticity during ramps.[^8][^4][^5]

Because these effects delay field stabilization, deteriorate harmonics, and waste power, strong avoidance and mitigation are standard design goals in fast-ramped accelerator magnets.[^2][^1]

Eddy current decay in accelerator magnets

Following a field step or the start of a flattop, induced currents do not vanish instantaneously but relax with geometry- and material-dependent time constants, often approximately exponential or multi-exponential in normal conductors due to the spectrum of diffusion modes in complex magnet and chamber geometries.[^9][^1]

An idealized decay can be written as , with scaling with magnetic diffusivity and a characteristic transverse dimension of the current loop, so in plate-like regions, leading to observable field creep on flattops as the eddy currents die out and the measured gap field rises toward the static value.[^9][^1]

In thick or non-circular beam pipes the response can show significant phase shifts and anisotropy (different in horizontal and vertical), requiring models that go beyond thin-wall approximations to capture shielding and delay correctly at the relevant excitation frequencies.[^5]

In superconducting magnets, cable-related persistent and inter-strand eddy currents can add slow or logarithmic-like decay components to the magnetization and field error evolution, strongly dependent on ramp history and conductor design.[^10][^6]

Minimizing eddy current decay in accelerator magnets

The primary lever is yoke lamination: using thin, insulated steel sheets with appropriate thickness for the excitation frequency window minimizes loop area and suppresses transverse currents, with typical accelerator guidance placing lamination thickness in the sub-millimeter regime for 10–50 Hz-class cycling.[^3][^2]

Interrupting current paths at magnet ends and in yoke end packs by adding slits and strategic segmentation reduces end-effects-driven loops; similar longitudinal slots or nonconductive inserts in vacuum chambers can suppress shielding currents, especially for fast-pulsed septa and kickers.[^11][^9]

Reducing, shaping ramps, and applying feedforward or pre-emphasis can compensate dynamic field errors during acceleration cycles, while passive or active correction windings placed on or near the chamber can counter eddy-current-induced multipoles.[^4][^1]

Design and verification rely on transient 3D field modeling and measurements, since laminated stacks, end regions, and realistic chamber geometries introduce coupling and harmonics that simple analytic formulas approximate only in limiting cases.[^12][^13][^11]

why avoidance is desired

Eddy-current-driven fields distort harmonics and degrade field quality in the good-field region, forcing longer settling times, complicating optics control, and reducing reproducibility under rapid cycling.[^1]

Losses increase power consumption and temperature, with particular risk in superconducting systems where added dissipation and coupling currents can trigger or complicate quench protection.[^6][^1]

Vacuum-chamber-induced multipoles and phase-lag effects can shift chromaticity and tune during ramps, necessitating additional correction and potentially limiting performance in high-intensity or fast-ramping machines.[^8][^4][^5]

Differential equation

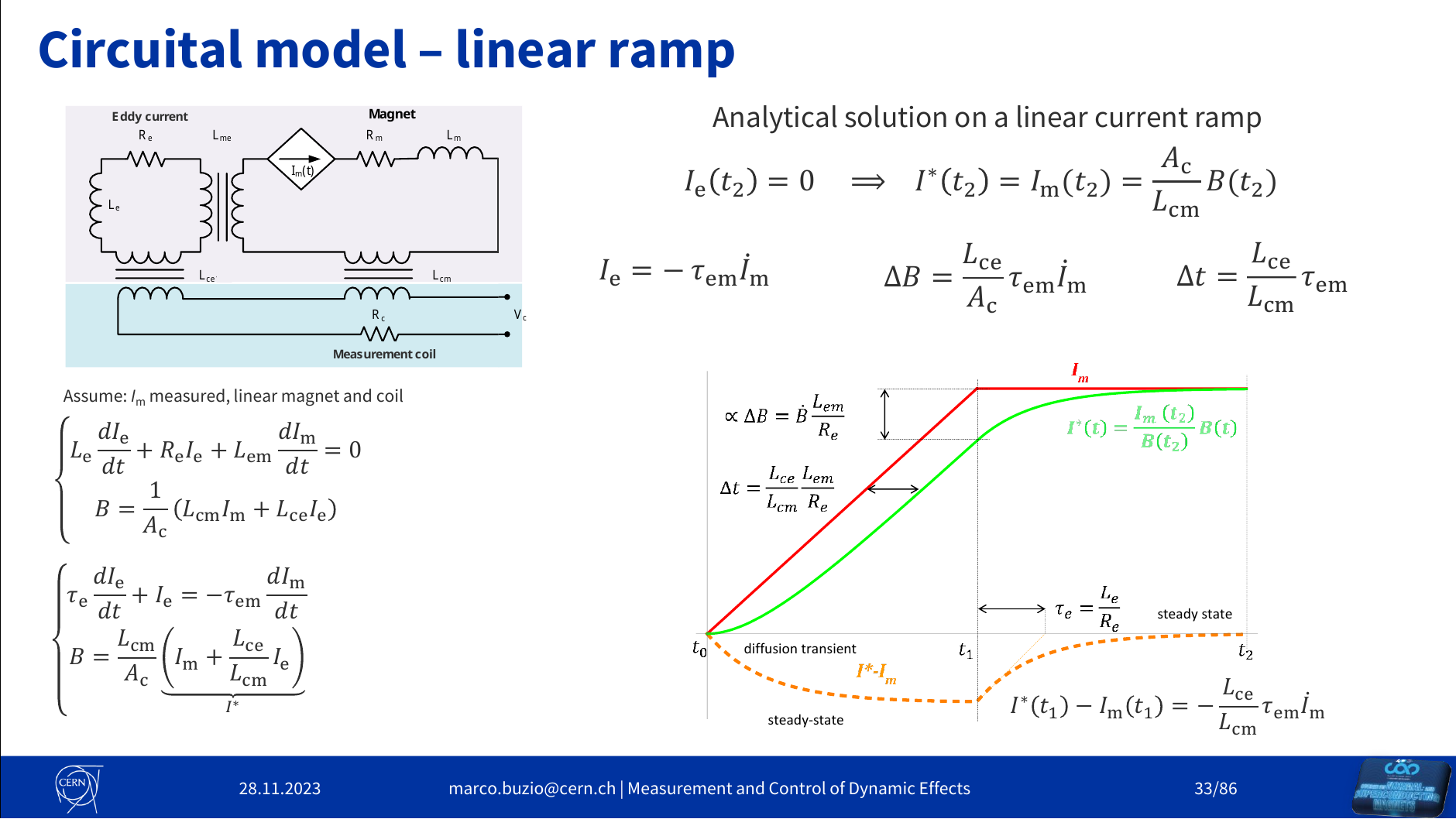

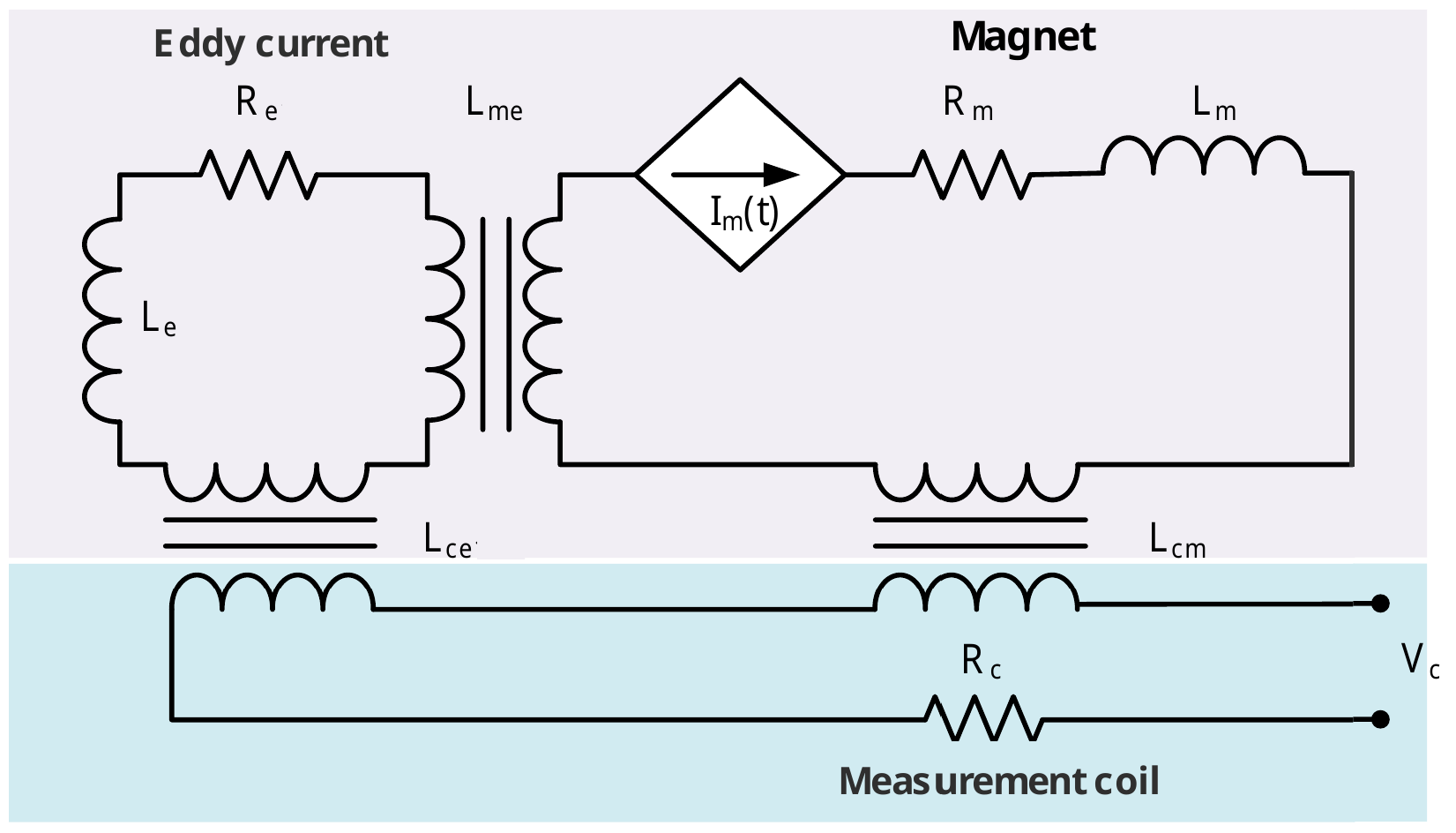

Assuming the circuit in the figure, where is the measured magnetization current, here with a linear magnet and coil. is the inductance of the magnet, the mutual inductance between the eddy currents and the magnet circuit, the inductance of the eddy currents, the mutual inductance between the measurement coil and the eddy currents, and the mutual inductance between the measurement coil and the magnet. The eddy current relationship can be described as

or equivalently

Identifying the constants and we see the equations as

Where is identified as the decay time constant, which means the time at which the value decays to of the original amount. For the SPS main dipoles, . Note here that the can be expressed as , which expresses the contributions from the external magnet current and eddy currents by the respective mutual inductances.

And eddy currents are added by a change in the magnetic field in the opposite direction through the coeffiecient . Assuming the response is large linear, we can express this as a function of the magnetising current, as explained by Marco.

Note that in reality the

Expressed in field

We can also express the eddy current differential equation in eddy current field contribution, assuming the relation , where according to the equations above, and a is a constant.

Solving the differential equation

We can make a general solution of the ODE as follows:

Write to standard form:

Introducing the integration factor

Applying the integrating factor and simplifying the equation using the integration factor we reach

And consequently

Discretization of the differential equation

The solution of the ODE confirms the findings of Mesure d’influence magnetique du cycle proton 450 GeV sur le cycle positron and Dipole Field, Tune and Chromaticity Correction at the SPS: from Converter Tracking to Eddy Currents which discretisizes the relation to

Where the only primary difference is the use of instead of , which obtain by multiplying by the derivative of the transfer function. Identifying the constants from the discretisized equation we find that and .

Implementation in code

We want to compute the integral:

This can be rewritten as a convolution between ( I(t) ) and an exponential kernel ( K(t) ):

where the kernel is defined as:

with ( \Theta(t) ) being the Heaviside step function, ensuring causality.

Discretized Form

For a discrete set of time points ( t_k ) with uniform spacing ( \Delta t ), the convolution can be written as:

A direct numerical summation has ( O(N^2) ) complexity, making it slow for large ( N ).

FFT-Based Convolution

Using the convolution theorem, we compute the integral efficiently by:

-

Taking the FFT of ( I(t) ) and ( K(t) ):

J_f = I_f \cdot K_f

J_k = \text{IFFT}(J_f)

Since FFT runs in **\( O(N \log N) \)** time, this method is much faster than direct summation. #### Implementation in Python ```python import numpy as np from scipy.fft import fft, ifft def exponential_convolution(I, t, tau): """ Compute the convolution of I(t) with exp(-t/tau) using FFT. Parameters: I (numpy array): The input function sampled at discrete times. t (numpy array): The time array corresponding to I. tau (float): The decay time constant of the exponential. Returns: J (numpy array): The result of the convolution. """ dt = t[1] - t[0] # Assuming uniform time spacing N = len(t) # Construct the exponential kernel K = np.exp(-t / tau) # Zero-pad both arrays to avoid circular convolution effects pad_length = 2 * N I_padded = np.pad(I, (0, N), mode='constant') K_padded = np.pad(K, (0, N), mode='constant') # Perform FFT-based convolution I_f = fft(I_padded) K_f = fft(K_padded) J_f = I_f * K_f J_padded = ifft(J_f).real # Inverse FFT to get convolution result # Extract the valid part of the convolution J = J_padded[:N] * dt # Multiply by dt to match integral scaling return J # Example Usage t = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000) # Time from 0 to 10 with 1000 points I = np.sin(t) # Example function tau = 1.5 # Decay constant J = exponential_convolution(I, t, tau) ``` #### Brute force integration Equivalent code can be written by solving the [[#differential-equation|Differential equation]] numerically: ```python def eddy_currents( H: npt.NDArray[np.float64], t: npt.NDArray[np.float64], tau_em: float, tau_e: float, c: float, Ie0: float = 0., ) -> tuple[npt.NDArray[np.float64], npt.NDArray[np.float64], npt.NDArray[np.float64], npt.NDArray[np.float64]]: dt = np.diff(t) dH_dt = np.gradient(H, t) Ie = np.zeros_like(H, dtype=np.float64) Ie[0] = Ie0 for i in range(len(t) - 1): dIe_dt = - tau_em * dH_dt[i] - 1 / tau_e * Ie[i] Ie[i + 1] = Ie[i] + dIe_dt * dt[i] Be = c * Ie return Be ``` #### Comparison of approaches ``` C = -8e-8 Be = exponential_convolution( I=np.gradient(H_precycle_interp, t_precycle_interp), t=t_precycle_interp, tau=1.3, ) * C tau_em = 0.1e-4 Be_disc = eddy_currents( H=H_precycle_interp, t=t_precycle_interp, tau_em=tau_em, tau_e=1.3, c=-C/tau_em, ) ``` ![[fig_eddy_current_compute_diff.png]] We see that in general we are below 2% error comparing the 2 methods, suggesting that the exponential is a quite useful method ### Field derivative driving eddy currents The proposed linear eddy current differential equation in [[#differential-equation|Differential equation]] uses $\dot{I}$ as excitation force for the eddy currents. However in reality the eddy currents are excited by changes in external magnetic field, $\dot{B}$. Plotting $\dot{I}$ and $\dot{B}$ overlayed we see that $\dot{B}$ remains proportional to $\dot{I}$ for most of the operational cycles, however as the magnet is close to saturation at high fields, the effective $\dot{B}$ is lower, hence it suggests that we instead must use $\dot{B}$ for calculation of eddy current decays. ![[fig_idot_bdot_calibrated.png]] ## Formalism ### Diffusion equation The following follows from the [[wiki:Eddy currents|wikipedia page]]. The derivation of a useful equation for modeling the effect of eddy currents in a material starts with the differential, magnetostatic form of [Ampère's Law](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ampère%27s_circuital_law), providing an expression for the [magnetizing field](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetizing_field) $\mathbf{H}$ surrounding a current density $\mathbf{J}$: $$ \nabla \times \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{J}.$$ Taking the curl on both sides of this equation and then using a common vector calculus identity for the curl of the curl results in $$\nabla \left( \nabla \cdot \mathbf{H} \right) - \nabla^2\mathbf{H} = \nabla \times \mathbf{J}.$$ From [[wiki:Gauss%27s_law|Gauss's law]] for magnetism, $∇ ⋅ \mathbf{H} = 0$, so $$-\nabla^2\mathbf{H}=\nabla\times\mathbf{J}.$$ Using Ohm's law, $\mathbf{J} = σ\mathbf{E}$, which relates current density $\mathbf{J}$ to electric field $\mathbf{E}$ in terms of a material's conductivity $σ$, and assuming isotropic homogeneous conductivity, the equation can be written as $$-\nabla^2\mathbf{H}=\sigma\nabla\times\mathbf{E}.$$ Using the differential form of [[wiki:Faraday%27s_law_of_induction|Faraday's law]], $∇ × \mathbf{E} = -\frac{∂\mathbf{B}}{∂t}$, this gives $$\nabla^2\mathbf{H} = \sigma \frac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t}.$$ By definition, $\mathbf{B} = μ_0(\mathbf{H} + \mathbf{M})$, where $\mathbf{M}$ is the magnetization of the material and $μ_0$ is the vacuum permeability. The diffusion equation therefore is $$\nabla^2\mathbf{H} = \mu_0 \sigma \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{M} }{\partial t} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{H}}{\partial t} \right).$$ ## references - Moritz, G., Eddy currents in accelerator magnets, CERN Accelerator School lecture notes. [^1] - Shcherbakov, P., 3D magnetic field and eddy loss calculations for iron (laminated yoke with end slits).[^11] - INFN School notes, Magnets in Particle Accelerators (laminated vs solid yokes).[^7] - USPAS notes, Magnet Fabrication (insulated laminations for time-varying magnets).[^2] - Holzer, B. J., Impact of persistent currents on superconducting magnets (history and decay).[^10] - Eddy Current Shielding by Electrically Thick Vacuum Chambers (dynamic response and phase).[^5] - Marks, N., A.C. Magnet Systems (lamination practice and thickness ranges).[^3] - PASJ, Field measurements and eddy current effects in a septum magnet (exponential decay and flattop creep).[^9] - BNL-AGS, Eddy current effect of the vacuum chamber on optics (sextupole, chromaticity during ramp).[^8] - PRAB, Secondary magnetic field harmonics vs vacuum chamber geometry (eddy-current harmonics).[^12] - Sorti et al., Data-driven modeling of nonlinear materials in normal-conducting magnets (iron-dominated dynamics context).[^13] - Fermilab TM, Chapter 6 Magnets (distortion scaling with thickness and conductivity; passive compensation windings).[^4] <span style="display:none">[^14][^15][^16][^17][^18][^19][^20]</span> <div style="text-align: center">⁂</div> [^1]: https://cds.cern.ch/record/1335027/files/103.pdf [^2]: https://uspas.fnal.gov/materials/12MSU/Lecture08.pdf [^3]: https://www.cockcroft.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/N_Marks_AC_Magnets_.pdf [^4]: https://lss.fnal.gov/archive/2001/tm/p-TM-21369.pdf [^5]: https://accelconf.web.cern.ch/pac2009/papers/th5pfp083.pdf [^6]: https://lss.fnal.gov/archive/2019/pub/fermilab-pub-19-843-td.pdf [^7]: https://agenda.infn.it/event/19098/attachments/62749/75362/PhD2019_Magnets.pdf [^8]: https://cds.cern.ch/record/553892/files/tha142.pdf [^9]: http://www.pasj.jp/web_publish/pasj4_lam32/PASJ4-LAM32/contents/PDF/FP/FP45.pdf [^10]: https://cds.cern.ch/record/399566/files/p215.pdf [^11]: https://accelconf.web.cern.ch/e06/papers/wepls094.pdf [^12]: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.16.082401 [^13]: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevAccelBeams.25.052401 [^14]: https://www.academia.edu/116602280/Eddy_currents_in_accelerator_magnets [^15]: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevAccelBeams.19.082401 [^16]: https://conferences.lbl.gov/event/2040/contributions/10023/attachments/5460/5421/Protection.pdf [^17]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0029554X73903881 [^18]: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168900218315304 [^19]: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/rsi/article/94/10/103308/2916714/Measurement-and-optimization-of-the-beam-coupling [^20]: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1910.09781.pdf